As a secondary teacher in Australia, school holidays are an opportunity to rest and regenerate. Sometimes they present opportunities to travel and encounter the lives and cultures of people far different from our own. In July I had the opportunity to visit Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), my first visit to this country. Any visitor can’t help but be struck by the landscapes dotted with golden pagodas and ancient temples. Along with opportunities to encounter the diverse cultural life of the people, my visit also gave me some moving and inspiring experiences of the transformative power of education.

Only in recent years has Myanmar emerged from decades of oppressive military rule. Even though civilian leadership and the opening up of the economy have encouraged social reforms and rapid development, the military continue to cast a strong and controlling shadow over political and economic life. Myanmar continues to suffer the legacies of this repressive rule: ongoing conflicts, forced displacement and widespread poverty. While the brutal campaigns against the Rohingya have caught the attention of western media, other ethnic minorities also continue to suffer from enduring conflict and the insecurity and harsh conditions of displacement camps. Health and education services for the general population have been neglected for decades. Yet the country has become one of the world’s top producers of heroin along with a growing trade in human trafficking. Too many people live on the margins, excluded from the opportunities of development and vulnerable to exploitation.

It is at these margins of society that the Myanmar Jesuit community focuses its efforts. Supported by Jesuit Mission, the Jesuits run education projects which give students access to quality education through scholarships, teacher training, language courses and two higher education institutes: St Aloysius Gonzaga Institute of Higher Studies (SAG) and the Campion Institute.

In Myanmar, the Jesuits are unable to offer the quality secondary education that distinguishes their schools in other parts of the world. Catholic schools were seized by the military government in 1965 as part of its nationalisation programme. The government continues to be responsible for primary and secondary schools but the quality of education is poor due to inadequate resources, facilities training and expertise. Passing by one primary school I was struck by the noise coming from the classrooms. The students in crowded classrooms were waving and throwing paper planes out the window. Surprised, I asked about this and was told many teachers had given up trying to teach as the power had been off for the past four hours, a regular occurrence. How else could it be in such heat with no light and no fans?

The Church in Myanmar has tried to address this situation through the development of boarding houses in parishes across the country to enable village children to attend the government schools and also receive supplementary lessons in the boarding homes. The Jesuit education programmes target students who often face barriers to accessing educational opportunities due to their ethnic background or economic and social circumstances. Hungry to acquire skills and knowledge, students also benefit from an Ignatian approach to teaching – developing critical thinking skills, striving to develop their full potential, actively discerning the best path forward and using their gifts and talents for the service of their community. This is a powerful and long-term vision of education as a vehicle to re-build a nation that values the lives of all its people.

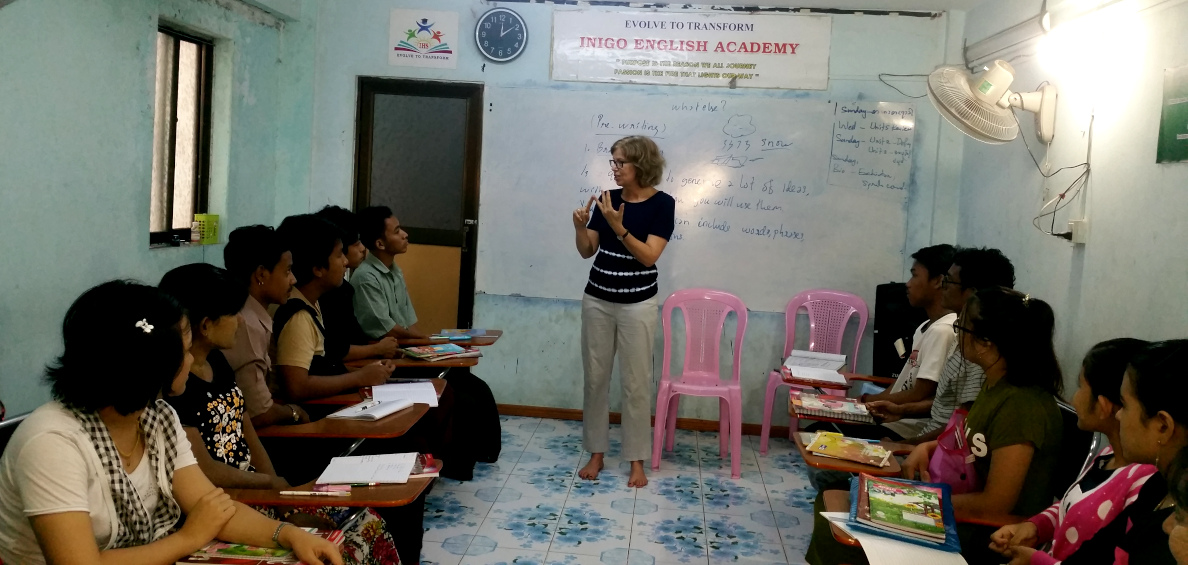

The Jesuits have also established the Yangon Loyola Community College which provides vocational training for young people who are usually excluded from access to such programmes. Training is provided in the areas of accountancy, computers, English and life skills. Work experience placements are also organised for the students. In its first year, 15 out of the 16 graduates were able to find full-time employment. Such a success has a profound impact on the young students, building their skills, confidence and engagement with the broader community. The Iñigo English Academy provides English language training in day, afternoon or evening classes. The classes are structured so that while learning English, the students experience and appreciate dialogue between the different ethnic and religious backgrounds. Such opportunities are significant in this ethnically diverse and often fractured society. The warm rapport between teachers and students nurtures a supportive learning community and helps to build the confidence of students. Between morning and afternoon sessions, the classroom is transformed into a dining area where teachers and students share their simple meals and conversation. Here, the divisions and prejudices experienced in broader society do not exist. Despite its humble surrounds and regular power outages, one quickly senses that the energy and commitment of all involved in this educational enterprise will transform lives and, hopefully, the society around them.

Louise Crowe is a teacher of Indonesian and Religious Education at Loyola College Watsonia with a long term interest in human rights and self-determination in Southeast Asia.

Louise Crowe is a teacher of Indonesian and Religious Education at Loyola College Watsonia with a long term interest in human rights and self-determination in Southeast Asia.

Related story: How education can shape a nation: the Jesuit commitment to peace and justice in Myanmar (part two)